RRADical Pd

| Author: | Frank Barknecht <fbar@footils.org> |

|---|

Abstract

The goal of RRADical Pd is to create a collection of patches, that make Pd easier and faster to use for people who are more used to commercial software like Reason(tm) or Reaktor(tm). RRAD as an acronym stands for "Reusable and Rapid Audio Development" or "Reusable and Rapid Application Development", if it includes non-audio patches, with Pd. It is spelled RRAD, but pronounced Rradical. ;)

What it takes to be a RRADical

RRAD as an acronym stands for "Reusable and Rapid Audio Development" or "Reusable and Rapid Application Development", if it includes non-audio patches, with Pd. It is spelled RRAD, but pronounced Rradical. ;)

The goal of RRADical Pd is to create a collection of patches, that make Pd easier and faster to use for people who are more used to software like Reason(tm) or Reaktor(tm). For that I would like to create patches, that solve real-world problems on a higher level of abstraction than the standard Pd objects do. Where suitable these high level abstractions should have a GUIs built in.

So for example instead of a basic lop~ low pass filter something more complete like a recreation of the Sherman filter bank could be included in that collection. My older sseq and angriff patches followed this idea in general, but there are much more patches needed. Like this:

- a sample player (adapt Gyre?)

- Various OSC/LFO with preset waveforms

- drum machine

- guitar simulator

- grain sample player

- more sequencers

- basically a lot of things like these things in Reason

Not that I want to make Pd be Reason, no way. But pre-fabricated high-level abstractions may not only make Pd easier to use for beginners, they also can spare lot of tedious, repeating patching work.

Problems and Solutions

To building above system several problems are to be solved. Two key areas already targetted are:

- Persistence

- How to save the current state of a patch? How to save more than one state (state sequencing)?

- Communication

- The various modules are building blocks for a larger application. How should they talk to each other. (In Reason this is done by patching the back or modules with horrible looking cables. We must do better.)

It turned out, that both tasks are possible to solve in a consistent way using a unique abstraction. But first lets look a bit deeper at the problems at hand.

Persistence

Pd offers no direct way to store the current state of a patch. Here's what Pd author Miller S. Puckette writes about this in the Pd manual in section "2.6.2. persistence of data":

Among the design principles of Pd is that patches should be printable, in the sense that the appearance of a patch should fully determine its functionality. For this reason, if messages received by an object change its action, since the changes aren't reflected in the object's appearance, they are not saved as part of the file which specifies the patch and will be forgotten when the patch is reloaded.

(I'll show an example of a float object changing "state" by a message in its right inlet here.)

Still, in a musician's practice some kind of persistence turns out to be an important feature, that many Pd beginners do miss. So there are several approaches to add it. Max/MSP has the preset-object, Pd has the state-object which saves the current state of (some) GUI objects inside a patch. Both also support changing between several different states.

Both have at least two problems: They save only the state of GUI objects, which might not be all that a user wants to save. And they don't handle abstractions very well, which are crucial when creating modularized patches.

Another approach is to (ab)use some of the Pd objects that can persist itself to a file, especially textfile, qlist and table, which works better, but isn't standardized.

A rather new candidate for state saving is Thomas Grill's pool external. Basically it offers something, that is standard in many programming languages: a data structure that stores key-value-pairs. This also is known as hash, dictonary or map. With pool those pairs also can be stored in hierarchies and they can be saved to or loaded from disk. The last but maybe most important feature for us is, that several pools can be shared by giving them the same name. A pool MYPOOL in one patch will contain the same data as a pool MYPOOL in another patch. Changes to one pool will change the data in the other as well.

A pool object is central to the persistence in RRADical patches, but it is hidden behind an abstracted "API", if one could name it that. I'll come back to haw this is done late.

Communication

Besides persistance it also is important to create a common path through which the RRADical modules will talk to each other. Generally the modules will have to use, what Pd offers them, and that is either a direct connection through patch cords or the indirect use of the send/receive mechanism in Pd. Patch cords are fine, but tend to clutter the interface. Sends and receives on the other hand will have to make sure, that no name clashes occur. A name clash is, when one target receives messages not intended for it. A patch author has to remember all used send-names, but this gets harder, if he uses prefabricated modules, which might use their own senders.

So it is crucial, that senders in RRADical abstractions use local senders only with as few exceptions as possible. This is achieved by prepending the RRADical senders with the string "$0-". So you'd not use send volume, but instead use send $0-volume. $0 makes those sends local inside their own patch borders. This might be a bit difficult to understand to the casual Pd user, but is a pretty standard idiom in the Pd world.

Still we will want to control a lot of parameters and do so not only through the GUI Pd offers, but probably also through other ways, for example through Midi controllers, through some kind of score on disk, through satellite navigation receivers or whatever.

This creates a fundamental conflict:

- We want borders

- We want to separate our abstraction so they don't conflict with each other.

- We want border crossings

- We want to have a way to reach their many internals and control them from the outside.

The RRADical approach adheres to this in that it enforces a strict border but drills a single hole in it: the OSC inlet. This idea is the result of a discussion on the Pd mailing list and goes back to suggestions by Eric Skogen and Ben Bogart. Every RRADical patch has (to have) a rightmost inlet that accepts messages formatted according to the OSC protocol. OSC stands for Open Sound Control and is a network transparent system to control audio applications remotely developed at CNMAT in Berkley.

The nice thing about OSC is that it can control many parameters over a single communication path. This is so, because OSC uses a URL-like scheme to address parameters. An example would be this message:

/synth/fm/volume 85

It sends the message "85" to the "volume" control of a "fm" module below a "synth" module. OSC allows many parameters constructs like:

/synth/fm/basenote 52 /synth/virtualanalog/basenote 40 /synth/*/playchords m7b5 M6 7b9

This might set the base note of two synths, fm and virtualanalog and send a chord progression to be played by both -- indicated by the wildcard * -- afterwards.

The OSC-inlet of every RRADical patch is intended as the border crossing: Everything the author of a certain patch intends to be controlled from the outside can be controlled by OSC messages to the rightmost inlet.

Trying to remember it all: Memento

To realize the functionality requirements developed so far I resorted to a so called Memento. "Memento" is a very cool movie by director Christopher Nolan where - quoting IMDB:

A man, suffering from short-term memory loss, uses notes and tattoos to hunt down his wife's killer.

If you haven't already done so: Watch this movie! It's much better than Matrix 2 and 3 and also stars Carrie-Anne "Trinity" Moss.

Here's a scene from "Memento":

We see the film's main character Leonard who has a similar problem as Pd: he cannot remember things. To deal with his persistence problem, his inability to save data to his internal harddisk he resorts to taking a lot of photos. These pictures act as what is called a Memento: a recording of the current state of things.

In software development Mementos are quite common as well. The computer science literature describes them in great detail. To make the best use of a Memento science recommends an approach where certain tasks are in the responsibility of certain independent players.

The Memento itself, as we have seen, is the photo, i.e. some kind of state record. A module called the "Originator" is responsible for creating this state and managing changes in it. In the movie, Leonard is the Originator, he is the one taking photos of the world he is soon to forget.

The actual persistence, that could be the saving of a state to harddisk, but could just as well be an upload to a webserver or a CVS check-in, is done by someone called the "Caretaker" in the literature. A Caretaker could be a safe, where Leonard puts his photos, or could be a person, to whom Leonard gives his photos. In the movie Leonard also makes "hard saves" by tattooing himself with notes he took. In that case, he is not only the Originator of the notes, but also the Caretaker in one single person. The Caretaker only has to take care, that those photos, the Mementos, are in a safe place and noone fiddles around with them. Btw: In the movie some interesting problems with Caretakers, who don't always act responsible, occur.

Memento in Pd

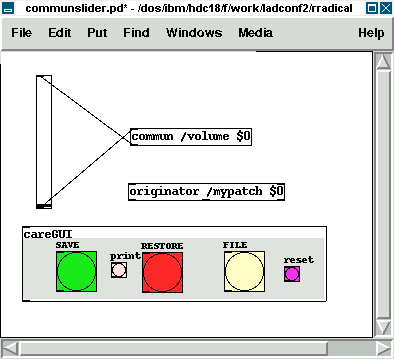

I developed a set of abstractions, of patches for Pd, that follow this design pattern. Memento for Pd includes a caretaker and an originator abstraction, plus a third one called commun which is responsible for the internal communication. commun basically is just a thin extension of originator and should be considered part of it. There is another patch, the careGUI which I personally use instead of the caretaker directly, because it has a simple GUI included.

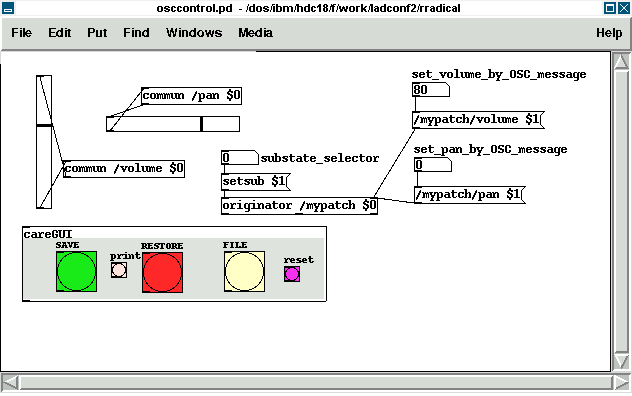

Here's how it looks:

The careGUI is very simple: select a FILE-name to save to, then clicking SAVE you can save the current state, with RESTORE you can restore a state previously saved. After restore, the outlet of careGUI sends a bang message to be used as you like.

Internally caretaker has a named pool object using the global pool called "RRADICAL". The same pool RRADICAL also is used inside the originator object. This abstraction handles all access to this pool. A user should not read or write the contents of pool RRADICAL directly. The originator patch also handles the border crossing through OSC messages by it's rightmost inlet. The patch accepts two mandatory arguments: The first on is the name under which this patch is to be stored inside the pool data. Each originator SomeName secondarg stores it's data in a virtual subdirectory inside the RRADICAL-pool called like its first argument - SomeName in the example. If the SomeName starts with a slash like "/patch" , you can also accesse it via OSC through the rightmost inlet of originator under the tree "/patch"

The second argument practically always will be $0. It is used to talk to those commun objects which share the same second argument. As $0 is a value local and unique to a patch (or to an abstraction to be correct) each originator then only can talk to communs inside the same patch and will not disturb other commun objects in other abstractions.

The commun objects finally are where the contents of a state are read and set. They, too, accept two arguments, the second of which was discussed before and will most of the time just be $0. The first argument will be the key under which some value will be saved. You should use a slash as first character here as well to allow OSC control. So an example for a usage would be commun /vol $0.

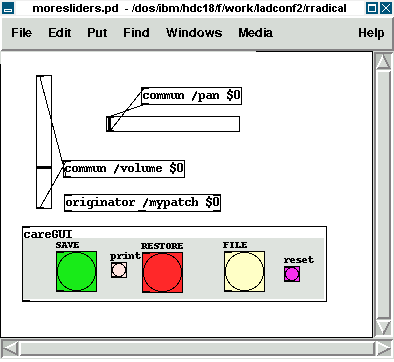

commun has one inlet and one outlet. What comes in through the inlet is send to originator who stores it inside its Memento under the key, that is specified by the commun's first arg. Actually originator. The outlet of a commun will spit out the current value stored under its key inside the Memento, when originator tells it to do so. So communs are intended to be cross-connected to some thing that can change. And example would be a slider which can be connected as seen in the next picture:

In this patch, every change to the slider will be reflected inside the Memento. The little print button in careGUI can be used to print the contents to the console from which Pd was started. Setting the slider will result in something like this:

/mypatch 0 , /volume , 38

Here a comma separates key and value pairs. "mypatch" is the toplevel directory. This contains a 0, which is the default subdirectory, after that comes the key "/volume", whose value is 38. Let's add another slider for pan-values:

Moving the /pan slider will let careGUI print out:

/mypatch 0 , /volume , 38 /mypatch 0 , /pan , 92

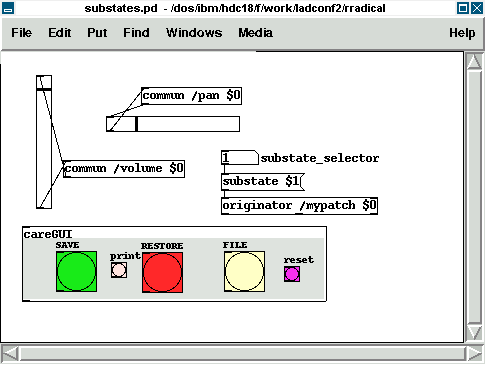

The originator can save several substates or presets by sending a substate #number message to its first inlet. Let's do just this and move the sliders again as seen in the next picture:

Now careGUI prints:

/mypatch 0 , /volume , 38 /mypatch 0 , /pan , 92 /mypatch 1 , /volume , 116 /mypatch 1 , /pan , 27

You see, the substate 0 is unaffected, the new state can have different values. Exchanging the substate message with a setsub message will autoload the selected state and "set" the sliders to the stored values immediatly.

OSC in Memento

The whole system now already is prepared to be used over OSC. You probably already guess, how the message looks like. Any takers? Thank you, you're right, the messages are built as /mypatch/volume #number and /mypatch/pan #number as shown in the next stage:

Sometimes it is useful to also get OSC messages out of a patch, for example to control other OSC software through Pd. For this the OSC-outlet of originator can be used, which is the rightmost outlet of the abstraction. It will print out every change to the current state. Connecting a print OSC debug object to it, we get to see what's coming out of the OSC-outlet when we move a slider:

OSC: /mypatch/pan 92 OSC: /mypatch/pan 91 OSC: /mypatch/pan 90 OSC: /mypatch/pan 89

Putting it all to RRADical use

Now that the foundation for a general preset and communication system are set, it is possible to build real patches with it that have two main characteristics:

- Rapidity

- Ready-to-use highlevel abstraction can save a lot of time when building larger patches. Clear communication paths will let you think faster and more about the really important things.

- Reusability

- Don't reinvent the wheel all the time. Reuse patches like instruments for more than one piece by just exchanging the Caretaker-file used.

I already developed a growing number of patches that follow the RRADical paradigm, among these are a complex pattern sequencer, some synths and effects and more. The RRADical collection comes with a template file, called rrad.tpl that makes deploying new RRADical patches easier and lets developers concentrate on the algorighm instead of bookeeping. Some utils (footils?) help with creating the sometimes needed many commun-objects. Several usecases show example applications of the provided abstractions.